A higher number of laboratory animals in Denmark is not necessarily negative (2018)

Comments by the Danish National Committee for the Protection of Animals used for Scientific Purposes/the Danish 3R-Center on the number of laboratory animals used nationwide

It is in the interest of the National Committee for the Protection of Animals used for Scientific Purposes/the Danish 3R-Center that the discussion about animals used for scientific purposes is an informed one. Accordingly, we give high priority to disseminating knowledge about laboratory animals and alternatives to them in our daily work.

In connection with the current publication of the number of laboratory animals being used nationwide, the Committee would therefore like to comment on the figure as it is necessary to be aware of a number of underlying matters to understand it. It often attracts attention when the number of laboratory animals used nationwide rises or falls. Increases are typically considered negative and decreases are considered positive. Things are not that simple in our opinion.

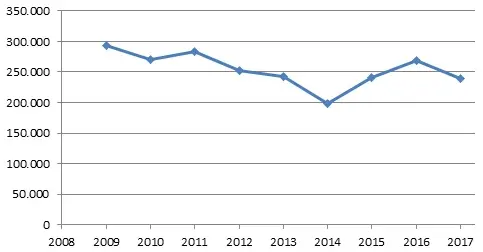

If we start by looking at the number of animals used in the period from 2009 to 2012 (fig. 1), we can see that the number has declined from 300,000 animals in 2009 to 250,000 animals in 2012. The decrease is almost solely attributable to two companies giving lower priority to their research activities (the companies are protected by anonymity, but their identity is known to us). In the period after 2012, two years stand out in particular, i.e. the decrease in 2014 and the increase in 2016.

The reason for the decrease in 2014 is attributable to changed reporting rules1 and the number (198,980) is consequently not comparable to the numbers in the preceding or the subsequent years. This means that the decrease is not due to research-based initiatives to reduce the number of animals used which would otherwise be positive, of course.

The 2016 increase is due to successful research relating to preserving eels as a species in the future. Scientists succeeded in breeding eels beyond the age of the larval stage which, unlike eel larvae, must be reported as research animals, resulting in the significant increase in the number of animals used.

Laboratory animals used in 2017

The number of laboratory animals used in 2017 is stated as 236,100, which means that the figure returned to the level at which it has been since 2012. With the above changes to the number of laboratory animals nationwide in mind, we can establish that the annual use of animals for scientific purposes in Denmark has stabilized at around 240,000–250,000 animals for many years. Though the number is not decreasing, the area of laboratory animals sees improvements on a daily basis. Scientists are thus making great headway for the 3Rs, but local laboratory animal improvements in the fields of Replacement, Reduction and Refinement become invisible when merely looking at the overall number of animals used nationwide.

A good example is Refinement – improvements that do not appear from the number of animals used nationwide but can be crucial for the welfare of the animals used for scientific purposes. If the near future should reveal a significant change to the number of animals used nationwide, this change will most likely be due to lower or higher research priorities being set by companies or at national level. Any research-based initiatives to reduce the number of animals used (Replacement or Reduction) will not necessarily have a significant effect on the national number, as another company may assign higher priority to research or new research activities can be set up in Denmark which may obscure this decrease.

Similarly, a focus on rises and falls in the absolute numbers reported does not reflect Reduction improvements of specific trials where the improvements did not lead to the use of fewer animals but resulted in a larger amount of knowledge obtained by the use of the same number of animals. According to Russell and Burch, this optimization of specific trials can also be considered to constitute Reduction.

Alternatives

Years ago, many were optimistic about the perspectives of replacing laboratory animals with alternatives, thereby drastically decreasing the number of animals used. In reality, there was probably only basis for optimism in the field of statutory safety testing of chemicals and medicinal products where the same type of tests is made on new substances, but which only accounts for a small part of the animals used for scientific purposes in Denmark.

The development of alternatives in other fields of research, for instance in connection with basic biological research and development of new therapies which account for a large proportion of the use of animals, has proven more difficult. There are many reasons for this. There are simply certain issues that currently cannot be resolved without using animals because it is not technically feasible to answer the research questions posted without using animal models.

So the issue is not a matter of a lack of will to introduce Replacement but rather a lack of the necessary knowledge at this moment in time.

In order to accelerate developments, it is important that established laboratory-animal scientists are encouraged to break with their deep-rooted habits and established tradition at the workplace so that the scientist does not automatically think in terms of animal models when setting out to resolve a research task, but seek alternative solutions from the outset.

The National Committee for the Protection of Animals used for Scientific Purposes naturally has a goal of replacing animals with equally suitable or better alternatives, and the Committee is, of course, working to both raise awareness of already existing alternatives and allocate research funds to Replacement projects.

As the development of alternatives is progressing at a slower pace than desired and a replacement of the majority of laboratory animals is probably not possible until years into the future, the National Committee for the Protection of Animals used for Scientific Purposes considers it to be most correct to also focus greatly on the two other Rs (Reduction and Refinement) in its work so that the number animals that are necessary to use can be minimized while ensuring their well-being at the same time.

1 The reporting rules for animals used for scientific purposes were changed in 2014. The most significant change was the introduction of a particular focus on the distress of the individual animal and any harm. This required the user of the animal to set up a continuous evaluation of the distress experienced by the individual animal during the trial period. And you could not submit the information about the animal before the trial was completed and you had the complete overview of the total and maximum distress for the animal.

As a consequence, the user could only report the use of the animal in the year in which the trial involving the animal ended, and not as soon as the trial began, as was previously the case. This meant that animals were included in trials in 2014 which would previously have been reported in 2014 but were now not released from the trial until 2015. Consequently, they were not included in the count until 2015. This resulted in a decrease in the total number of animals used for scientific purposes in 2014. Only when the figure for 2015 was available did we have new data for a 12-month period that allowed us to compare the annual use of laboratory animals again.

Newsletter

Sign up for our newsletter - don't miss information about our annual symposium etc.